A large dance hall at 188 rue de l'Université in

Paris took place in Magic-City. That was known for its "

drag balls."

The emblematic event of homosexual life in Paris in the inter-war years was a series of masked balls held annually during Carnival on

Mardi Gras (

Shrove Tuesday) and

Mi-Carême (Mid-

Lent) at Magic-City Dancing, an immense dance-hall on the Rue de l'Universite, near the Eiffel Tower. ... Between 1922 and 1939, thousands of men, most costumed and many in extravagant female drag, attended the balls at Magic-City every year. 'On this night,' wrote a journalist in 1931, 'all of Sodom's grandsons scattered throughout the world...seem to have rebuilt their accursed city for an evening. The presence of so many of their kind makes them forget their abnormality.' Gyula

Brassaï, whose photographs have immortalized these fabulous balls, described the 'immense, warm, impulsive fraternity' at Magic-City:

The cream of Parisian inverts was to meet there, without distinction as to class, race or age. And every type came, faggots, cruisers, chickens, old queens, famous antique dealers and young butcher boys, hairdressers and elevator boys, well-known dress designers and drag queens...[4]

It was closed by the authorities on February 6, 1934,[5] and in 1942 the building was bought by the government and turned over to Paris-Télévision, which began broadcasting from there in 1943.[6]

Home › When Paris Met the Mahatma

When Paris Met The Mahatma

POULBOT / LE COUP DE PATEA 1931 cartoon published in France depicting Gandhi on his voyage to Geneva via Paris and a French woman offering Gandhi trousers of honour. - See more at: http://caravanmagazine.in/reporting-and-essays/when-paris-met-mahatma#sthash.9LBtSBlQ.dpuf

0

0

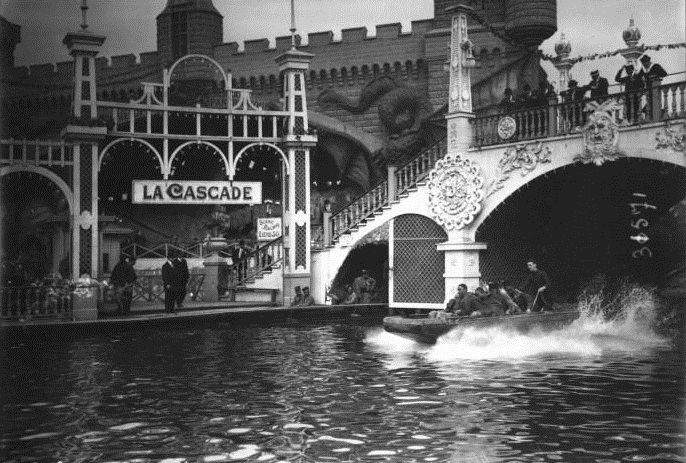

MAGIC CITY WAS A LARGE DANCE HALL on Paris’s Left Bank, used over the decades for purposes as diverse as transvestite balls in the roaring 1920s and the storage of Jewish property confiscated by the fascist French government in the 1940s. It was seized by the Nazis and lavishly refurbished as a radio studio run by the Gestapo during the Occupation, and it was where French television broadcasting set up shop during the 1950s.

It was also the place where Mahatma Gandhi—on his way home from the Second Round Table Conference in London and en route to visit Romain Rolland in Geneva—made his only public appearance in Paris, on 5 December 1931, in the very same space where the celebrated Parisian drag queens Kymris and Monsieur Bertin once strutted their stuff.

According to contemporary newspaper accounts of the event, it was a strange evening. Patrons were ushered to their seats by girls “bizarrely uniformed in bright red skirts, leather boots, and wide leather belts from which hung cutlasses”, according to the journalist Robert Gauthier’s report in Le Temps. Gauthier observed that the “atmosphere, part circus, part dancing hall, the overheated room, the massive columns of red marble, the flashes of magnesium from here and there, and the floodlights ready to be lit into action were not on the same level as this leader of men.”

Further to the right, reporter Georges Suarez had a different take in L’Echo de Paris: “Mahatma Gandhi proves himself to be a great comic.... He appears crushed by his lamentable half-nakedness ... but, if his sandals are those of Mohamed, his little bathing suit does not conjure up Napoleon’s coat at Wagram.” According to Muriel Lester’s Entertaining Gandhi, an account of her travels with the Mahatma in Europe, Suarez was angry that he’d been denied a tête-à-tête interview with Gandhi earlier in the day after he snuck into the apartment where Gandhi was staying on Boulevard Raspail. He promised Lester he’d write nasty things about Gandhi if he wasn’t given access to the man, and he did.

By the time Gandhi arrived in France in 1931, he was an international celebrity. His 1930 Salt March had been widely covered by the foreign media—whose interest in the proceedings was mocked in a book-length satirical poem, called The Saint and Satan, published the same year:

At once the Press entire took up the chorus

And pestered every mile that lay before us;

The Press entire, becoming shrill and shriller,

Published each day some more exciting thriller;

They soon grew indiscreet and indiscreeter;

Sugar was sweet, but contraband salt was sweeter!

William L Shirer, then a correspondent with the Chicago Tribune, described the Salt March in his book, Gandhi: A Memoir, as “one of the strangest treks ever witnessed in India or in any other country. And it soon became one of the most reported, as dozens of Indian reporters joined the two or three local reporters who were in at the outset, followed by correspondents from all over the world.” United Press correspondent Webb Miller’s description of silent satyagrahis at the Dharasana Salt Works north of Bombay coming forward to be brutally whacked down by lathi-armed police was, according to Shirer, “flashed around the world—Miller’s graphic United Press dispatch was published in more than a thousand newspapers at home and abroad.”

In January 1931, Time magazine put Gandhi on its cover and named him Man of the Year. French newsreels had shown footage of the Salt March, which was also widely reported in the French press. When Gandhi landed in Marseilles on 11 September 1931 on his way to London, he was mobbed by reporters. In fact, the second supplemental volume of Gandhi’s Collected Works reproduces no fewer than seven press statements made by Gandhi in Marseilles—a city where he did not even pause long enough to spend the night—to the Daily Herald, the New York Times, the Bombay Chronicle, the Daily Mail, the Associated Press, the News Chronicle and Reuters. From the moment he arrived on European soil until his departure for Bombay from Italy, wherever Gandhi went, the press followed. Their dispatches, photos and films appeared around the world. By 1934, Cole Porter could write lyrics for his Broadway hit musical Anything Goes declaring, “You’re the top! You’re Mahatma Gandhi.”

After the excitement of Gandhi’s brief stop in Marseilles, French papers and newsreels were filled with images from London of the diminutive and scantily clad Gandhi speaking to crowds of cheering British workers, on his way to meet the king of England or seated next to a beaming Charlie Chaplin. Outside Magic City on the evening of his speech, there was pandemonium. Tickets had been given out judiciously, to a lucky 2,000 people, and a crowd of hundreds mobbed the entrance, hoping to get in, or simply to catch a glance of the famous Indian. Even journalists with tickets and press passes had trouble at the door: the Le Figaro correspondent Gaëtan Sanvoisin, clearly a man not used to summary treatment, grumbled in his report about being hassled at the door, lamenting that the police were no help, as they were taking orders from “young men wearing blue-starred armbands”, apparently hired to help manage the crowd.

Inside, Gandhi was seated on the stage, accompanied by Madeleine Slade, whom he called Mirabehn—the daughter of a British rear-admiral and one of his most devoted disciples. He spoke in English, uttering a few sentences at a time, which were promptly translated into French. Press accounts from the right and the left were unanimous in their surprise at the apparently passive demeanour of the speaker, whose voice was described as “monotone” and who barely looked up at the audience while he spoke. Clearly, Gandhi was not as entertaining as the usual performers at Magic City, or perhaps his quiet delivery didn’t match his outsized reputation. Given that he had arrived from London earlier in the day by train and had already held two meetings—a lavish tea with the cream of Indian society in Paris and an informal meeting of “intellectuals” (in the words of Gandhi’s secretary, Mahadev Desai) at the tiny apartment of his hostess, Louise Guyiesse—he was probably exhausted.

A brief audio snippet from Gandhi’s speech at Magic City survives, in a newsreel produced by Pathé-Journal titled “Gandhi’s Visit to Paris”. In a firm voice, Gandhi declares, “It seems to me the world has become sick of blood-thirsty war. The world is disgusted with the lies and deceit that are the inevitable consequences of all war-like methods.” He pauses for his French translator, and as soon as the translation is finished, the audience erupts in applause. According to Robert Gauthier in Le Temps, this was all part of the staging: “Disarmament was the order of the day,” he sniffed, “and while propagandists distributed tracts and brochures among the audience, others passed along to Gandhi written questions which offered him the chance for easy applause.” Writing for the conservative Le Figaro, Sanvoisin was alarmed, rather than amused, by the sight of an Indian advocating independence from an imperial European power: Gandhi’s words, he warned his readers, “were nothing if not dangerous, and that is what the French public needs to know.”

Mahadev Desai transcribed some of the questions from the audience, as well as remarks Gandhi addressed to expatriate Indians. The questions ranged from whether independent India would put up trade barriers with France to why Gandhi no longer wore European clothes. Gandhi’s Collected Works contain a long, but incomplete, version of his full remarks at Magic City, which have been translated back into English on the basis of a French translation of his speech published in a January 1932 special issue of the magazine Régénération dedicated to Gandhi and India. The portion of the speech quoted in Le Figaro by Sanvoisin places the short surviving section recorded from the newsreel into the wider context that Gandhi gave it:

I tried to understand your great revolution, but I think that you want to address a greater message to the world because the Earth is tired of sanguinary wars. The universe is disgusted with the hypocrisies that are the necessary consequences of bellicose methods. The economic crisis which is tearing countries apart, not excepting the United States, is a consequence of the global conflagration, which we have been sufficiently mistaken to call the ‘Great War.’

Go to Page:

View as

- See more at: http://caravanmagazine.in/reporting-and-essays/when-paris-met-mahatma#sthash.9LBtSBlQ.dpuf

No comments :

Post a Comment